Coffee was a new fashionable drink in the late 17th century. Along with tea and chocolate, it was one of the drinks coming into England from around the world. Maritime trade had expanded, as had England’s influence on the world, and conversely, the world’s influence on England. Coffee had been consumed in the Ottoman Empire for many years and was slowly making its way into Europe in the early 17th century. The first coffee house in England was established in Oxford around 1650 by a Lebanese Jew named Jacob, but little is known about him or his business. That was the first evidence for a coffee house, but it would already have been drunk in the more affluent households as a curiosity. The process of producing it was unknown, and the early coffee lovers, before the coffee houses were established, would have had to employ people who knew how to roast the beans, grind them and brew it, so it would still have been quite an exclusive drink.

The first London coffee house was known as “the Turk’s Head”, which was located in the alleyways between Lombard Street and Cornhill. Pasqua Rosee was the proprietor. The story has it that he worked for Daniel Edwards, who was a merchant in the Levant Company. Edwards had developed a taste for coffee and, on returning to England, brought his coffee-making servant, Pasqua, with him. Whilst Edwards stayed in London with his friend Thomas Hodges, Pasqua would make coffee for the Hodges family, friends and business connections when they visited the house. It became so popular within their circles that the house was overrun with visitors who wanted to drink this coffee. Thus, the idea of selling it outside came to them. At first, a stall was put up in St Michael’s Churchyard, in Cornhill, which was followed by an actual coffeehouse being opened around the corner in St Michael’s Alley.

Unlike the traditional drinks drunk in England, beer and wine, coffee didn’t get you drunk or lightheaded. In fact, it had the opposite effect. It sharpened the mind and was very good for business. It was advertised as such that coffee “will prevent drowsiness and make one fit for business”. Merchants, traders, and stock-jobbers liked this drink, and the coffee houses gave them a place where they could work without drunkenness and mayhem around them.

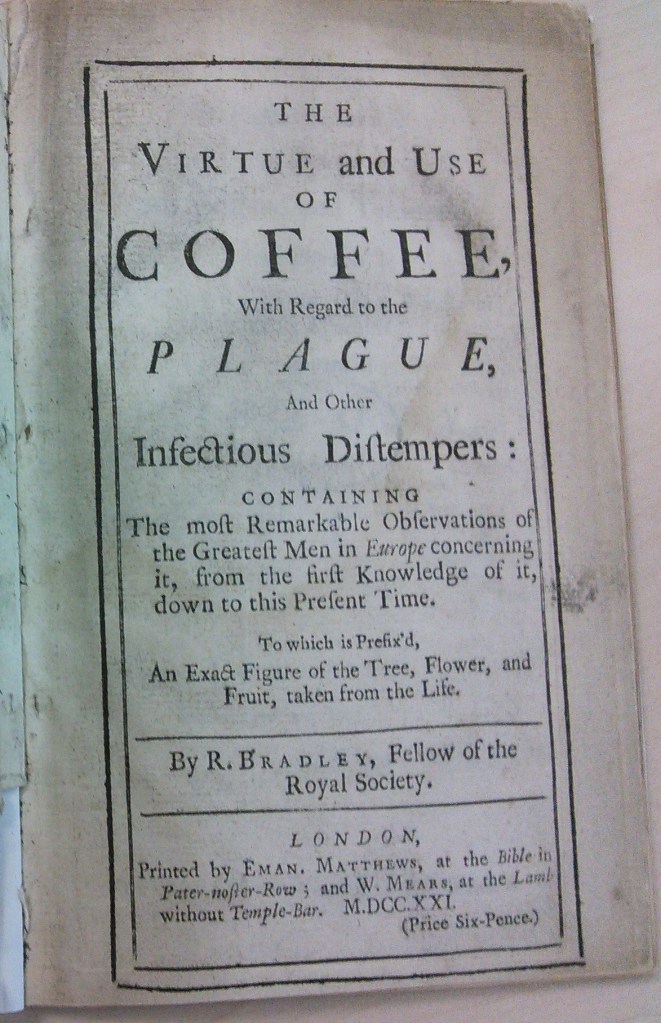

There are various reports of coffee being good and bad for you. In 1721, R. Bradley, Fellow of the Royal Society wrote a pamphlet, The Virtue and Use of COFFEE With Regard to the PLAGUE and other Infections and Distempers.

Tavern, inn and ale-house owners (although any gentleman would not be found in an ale-house), campaigned against coffee as it took custom away. Charles II didn’t like the idea of coffee houses, as they could be places of dissent and plotting into the night, and the drink kept the conspirators awake, instead of falling into a drunken slumber. Charles tried to close the coffee houses down in 1675, but met with overwhelming objections from the coffeehouse patrons. He backed down.

Women had different views. On the one hand, it was good that husbands did not return from the City drunk, but awake and full of spirits. On the other hand, there was a campaign against it, with people not trusting this new brew from abroad. A pamphlet was produced in 1674, which claimed coffee made men sterile, “as unfruitful as the deserts whence that unhappy berry is said to be brought”. In Venice, some called it the ‘bitter invention of Satan,’

What was the 17th century coffee like?

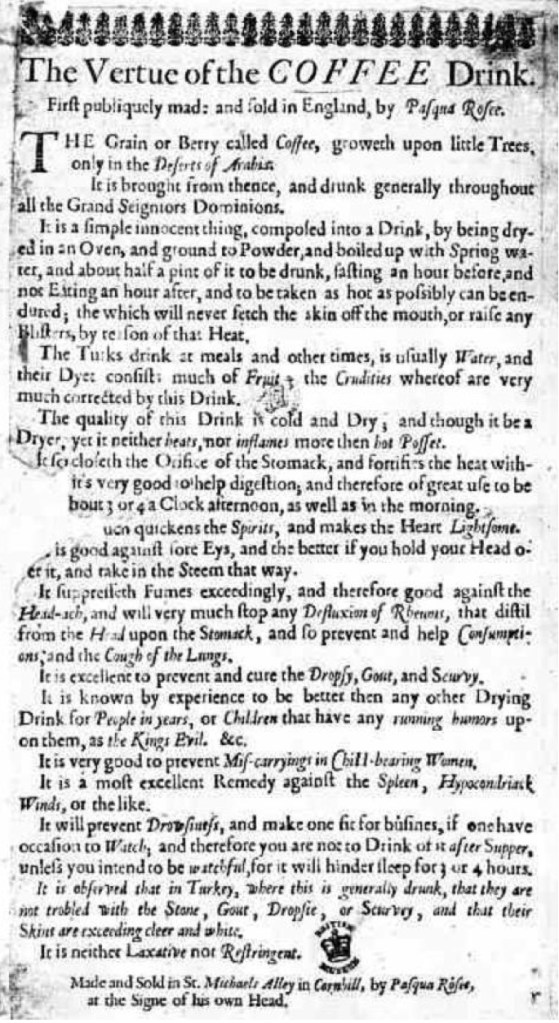

What was this new drink like? A handbill of the time, printed around 1652, describes the drink for those unfamiliar with coffee. The handbill promoted it in a very positive light, discussing its background, how it is prepared and the health benefits. There is a description, “the quality of this Drink is cold and Dry; and though it be a Dryer, yet it neither heats, nor inflames more than hot Posset.” A translation of the handbill is below.

The handbill was essentially an advert for Pasqua Rosee’s Coffee House. At the bottom of the bill, it tells you where to find the coffee, “Made and Sold in St. Michaels Alley in Cornhill, by Pasqua Rosee, at the Signe of his own Head.”

It is obvious to say that the coffee we have today is in no way the same as the coffee of the 17th century; all the same, it is worth pointing out. To start, there were no lattes, Americanos, or cappuccinos, nor the creativity of new “coffees”. Making coffee under high pressure in a coffee machine is a 20th century development. On top of that, the quality of the beans would have been very different. Their production was labour-intensive, hand-picked by enslaved people on the plantations in South America and the Caribbean. They were packed and stored in hessian sacks, transported to Europe on the slow sailing ships, and processed into coffee powder in the coffee houses themselves. Today, our coffee beans are swiftly picked, transported around the world, vacuum-packed and frozen to keep freshness.

Pasqua’s handbill describes how to process it:

“It is a simple innocent thing, composed into a drink, by being dry-ed in an Oven, and ground to Powder, and boiled up with Spring water, and about half a pint of it to be drunk, fasting an hour before and not Eating an hour after, and to be taken as hot as possibly can be endured; the which will never fetch the skin off the mouth, or raise any Blisters, by reason of that Heat.”

There was no strict standard recipe or specific ways of making coffee, and coffeehouses would have their own distinct coffee taste. Another contemporary description of making coffee states:

“Take a gallon of faire water & boyle it until halfe be wasted, & then take of that water one pinte, and make it boile, & then put in one spoonefull of the Powder of Coffee & let it boyle one quarter of an houre, stirring of it two or three times, for feare of running over, & drink it as hot as you can.”

This is from The Recipe Book 1659-72 of Archdale Palmer, Gent. Lord of the Manor of Wanlip in the County of Leicestershire.

I presume the initial boiling of the water ensured it would be safe to drink. Water supply in cities at this time was not a healthy source of drinking water. Going back to Pasqua’s recipe, he says to use “Spring water”, which would have been unpolluted from sewage. As Pasqua says, making coffee in a 17th century style is a straightforward process. Here’s what to do.

Choose your beans

If you do not want to roast the beans yourself, then choose your pre-roasted beans and skip to the ‘Grind your coffee beans‘ section. I recommend fairtrade, which most brands tend to be today, and to get that authenticity, try organic. Early European coffee was imported by the Dutch East India Company from Java and Ceylon, but the earliest references to coffee show it was grown in Yemen in the 16th century.

If you do want to roast the beans yourself, there are many suppliers of green coffee beans.

Roast your beans

Roast the green beans in a frying pan or skillet over a fire. Once the fire gets going, stir your beans until you start to hear them make a ‘cracking’ sound, similar to popcorn. Keep stirring them – it only takes a couple of minutes.

I think a point to be made here, is about the smell of roasting. It fills a building with an intense smell of coffee. Going back to those streets in London around 1700, think of that intense potent smell coming out of the doorwars and into the lanes. It must have been part of the daily make up of the City of London.

Grind your coffee beans

Grind your coffee beans into a coarse powder with a pestle and mortar. It is estimated that a 17th century cup of coffee was made with 30 to 50 grams (one or two ounces) of coffee per cup (about 235 ml or 8 fluid ounces).

Boil your coffee

Boil your coffee powder in water for about 15 minutes. Some coffee houses would boil it for longer, up to an hour. If you look at images of 17th century coffee houses, you will see large pots over the fire, which boiled the coffee, and tall coffee pots in front of the fire, keeping warm. It is more akin to a coffee you might make on an open fire, or some say a Turkish coffee, although Turkish coffee does not take as long to boil.

Drink your coffee

Coffee was served in tall coffee pots and poured into small bowls, without a handle. If you wish to extend the experience and immerse yourself, wear a frock coat, long waistcoat, cravat, stockings, and a full-bottomed periwig. If you want to dress as a 17thcentury woman, then consider a fontange on your head with a gown and stomachers pinned onto a pair of stays.

Quality

Some people hated it. One poem describes it as “syrup of soot” or “essence of old shoes”. This may have been part of the lobby against coffee. I often think what it would have been like to taste for the first time; what was that very first sip like? A drink that had never been drunk in society before. It was black, bitter and must have taken time to develop a taste for it.

But as a saying in my family goes, “proof of the pudding is in the eating”, and it caught on, so it was obviously liked and enjoyed. Coffee Houses promoted themselves as purveyors of the best quality to attract customers:

“Will’s Best Coffee Powder at Mannarings Coffee House in Falcon Court over against St Dunstans Church in Fleet Street.”

I am not sure who Will was, but perhaps he was making a name or brand for himself as the maker of the best coffee.

The most wily and entrepreneurial of coffee house owners did not solely rely on their coffee to attract customers. They would also sell tea, chocolate and sherbert, all drinks. Many of the coffee houses would also have the latest news, broadsheets, gazettes and specialist information, such as the ships’ lists (The Coffee House Ships Lists).

For now, Good Luck with your coffee.

References

Clayton, Anton, 2003, London’s Coffee Houses. London: Historical Publications.

Robinson, H and Adams, W., 1935, The Diary of Robert Hook. London: Taylor and Francis.

Ukers, William Harrison, 1922, All about coffee. New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Co

Pasqua Rose: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pasqua_Ros%C3%A9e

The Vertue of the COFFEE Drink. First publiquely made and sold in England, by Pasqua Rosée.

THE Grain or Berry called Coffee, groweth upon little Trees, only in the Deserts of Arabia. It is brought from thence, and drunk generally throughout all the Grand Seigniors Dominions.

It is a simple innocent thing, composed into a drink, by being dry-ed in an Oven, and ground to Powder, and boiled up with Spring water, and about half a pint of it to be drunk, fasting an hour before and not Eating an hour after, and to be taken as hot as possibly can be endured; the which will never fetch the skin off the mouth, or raise any Blisters, by reason of that Heat.

The Turks drink at meals and other times, is usually Water, and their Dyet consists much of Fruit, the Crudities whereof are very much corrected by this Drink.

The quality of this Drink is cold and Dry; and though it be a Dryer, yet it neither heats, nor inflames more than hot Posset. It forcloseth the Orifice of the Stomack, and fortifies the heat with-[in (missing text) that] it’s very good to help digestion, and therefore of great use to be [(missing text) taken a]bout 3 or 4 a Clock afternoon, as well as in the morning. [(missing text) It very m]uch quickens the Spirits, and makes the Heart Lightsome. [(missing text) It] is good against sore Eys, and the better if you hold your Head o-[v]er it, and take in the Steem that way.

It supresseth Fumes exceedingly, and therefore good against the Head-ach, and will very much stop any Defluxion of Rheums, that distil from the Head upon the Stomack, and so prevent and help Consumptions; and the Cough of the Lungs.

It is excellent to prevent and cure the Dropsy, Gout, and Scurvy. It is known by experience to be better then any other Drying Drink for People in years, or Children that have any running humors upon them, as the Kings Evil. &c.

It is very good to prevent Mis-carryings in Child-bearing Women.

It is a most excellent Remedy against the Spleen, Hypocondriack Winds, or the like.

It will prevent Drowsiness, and make one fit for Busines, if one have occasion to Watch, and therefore you are not to drink of it after Supper, unless you intend to be watchful, for it will hinder sleep for 3 or 4 hours.

It is observed that in Turkey, where this is generally drunk, that they are not trobled with the Stone, Gout, Dropsie, or Scurvey, and that their Skins are exceeding cleer and white.

It is neither Laxative nor Restringent.

Made and Sold in St. Michaels Alley in Cornhill, by Pasqua Rosee, at the Signe of his own Head.

From a 1652 handbill advertising coffee for sale in St. Michael’s Alley, London. It is held in the British Museum. Missing text inserted from an 1863 reprinting found in ‘The book of days, a miscellany of popular antiquities’ pages 170-171

I need to look out my fontage.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It makes me very happy that you have one.

LikeLike