An important peace treaty and charter was agreed and sealed at the beginning of the 13th century, that isn’t talked about that much today. It is tantalisingly possible to track down the exact place and the day it all happened on. The treaty of Kingston was agreed on an “island on the River Thames at Kingston”. Along with the agreement on peace, the Magna Carta was re-issued and a new charter, The Forest Charter, was written confirming the freeman of England’s rights of the forest which they had recently lost.

It all started with “Bad King John”. My favourite summing up of John was by L. du. Garde Peach:

“King John was probably the worst king ever to mount the English throne. He was cruel and treacherous, a boastful coward; mean and deceitful as a man, utterly untrustworthy as a king. He died loathed by everyone who knew him, regretted by none.”

John’s rule had divided England. The Barons revolted against him in the early 1200s, and in 1215 the Magna Carta was created to curb his activity and restore powers to the Barons. He immediately rescinded it and went back to war with the Barons. The Barons invited Prince Louis of France to replace John as king, Louis landed in England in 1216 and not long afterwards John died in Norfolk whilst on campaign.

John’s son Henry became king at the age of 9 with William Marshall, acting as guardian. Marshall was one of the most famous knights in England, a soldier, an excellent politician and strategist. Henry’s coronation was rushed through with Cardinal Guala Bicchieri overseeing it at Gloucester Cathedral. This was an opportunity for all to re-unite England and after all, the young King Henry III, under Marshall’s guidance, was not John. With this in mind, some of the rebel Barons started to come over to the royalist side.

Prince Louis remained in England, continuing the rebellion and his claim to the throne. In May 2017, William Marshall met Louis’ forces at the Battle of Lincoln. Marshall was outnumbered, but won the battle. There were further defeats for Louis that year. The first was at Dover Castle, a key stronghold. The second was the Battle of Sandwich, where the French fleet was defeated. Marshall went on to blockade London by sea and land. London played a key role in the rising against the King and remained steadfast in their support for Prince Louis. In fact, when the Prince landed in May 1216, he made straight for London.

The Peace

By late August, Louis was forced to negotiate. Parleys between the two sides had started around 28th August and by early September, direct contact had been made between William Marshall and Louis. Negotiations proved to be difficult and at one point looked like breaking down with a return to civil war. The talks were spread over several locations, starting at Staines, where the Royalist camp was at the time, and finishing in Rochester. My question is, where and when did the negations taking place in Kingston?

When? “From the day that these things will be established in peace”

“A die qua firmabitar pax ista” (the above quote) is a reference in a text to the day when the peace negotiations were agreed. Unfortunately, it does not give an exact date.

Historical sources can be scant, especially when looking at earlier times. It isn’t that people didn’t keep records, but that they have been destroyed or lost. The longer something exists, the greater the risk that it has of being burnt in a fire, re-used as something else, lost or sold. The original treaty does not exist.

The interpretation of documents can also prove to be ambiguous. Today, we use exact dates, and times. Medieval documents were recorded as being in the year of a reign, for example, a reference to a year could be “the third year of Henry III”, which will be 1219. One of the sources for the date of the peace treaty gives us a date as being the Tuesday before the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

Because the event is not a famous one, not much time has been spent on identifying when it took place. I’ve looked to many sources for confirmation, although not had the time to travel to interrogate the primary sources, which are found in England and France. There is no one document that will confirm the date absolutely. Much online is brief and copied from one website to another.

Beverley Smith in an article in 1979, has assessed the evidence and gives the 12 September for the peace treaty being agreed in Kingston. From what I’ve read, it seems the most plausible. The sources she has interrogated include the Histoire des Ducs de Normande and a Merton annalist, from Merton Priory, which played a part in the negotiations. It is the Peniarth-Pont Audemer text that refers to the Tuesday before the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, which Smith points out is the 12 September. Supporting this date further, the Merton annalist records that Louis and many magnates of France were absolved on the island near Kingston on 13 September, the day after.

After much reading in the library and online, I decided to go with 12 September. I have published this piece on 12 September 2017, exactly 800 years on from when the peace treaty was agreed in Kingston. Although, was it actually on this day? Not as such. It was on 12 September, but not our 12 September. In the 18th century England went from using the Julian to the Gregorian Calendar. There was a shift in days to account for the change, and to find the day in our calendar when the negotiations took place, we should bring it forward seven days. That makes it the 5th September, our time.

Where? “On an Island at Kingston”

The texts don’t specify which island. Today, there are two islands on the river at Kingston and a few more if you travel a little distance up or downstream.

These are aits, which are small islets formed by sediment, sand and gravel, deposited by the river current. These deposits in turn collect more sediment to form a small island. The ait can become permanent, they can move over time, or be eroded away with the sediment moving slightly down stream, possibly forming a new ait elsewhere. The earliest map I know of Kingston from the 17th century shows a number of aits, although Ravens Ait is off the map, to the south.

Locally, people do not know too much about the peace treaty, if they know about it at all. It is generally believed that the treaty was negotiated on Ravens Ait. Was it Ravens Ait? No-one can really say, but it is the most likely of the islands. It is a substantial ait along the River by Kingston and it is in the local collective memory as being the island. If it was, has Ravens Ait moved since 1217? It could have. In recent history, the island has been shored up with iron girders and is now stable with buildings upon it.

Why an island?

Why would an island be chosen to meet and agree an important peace treaty? There were many establishments where a treaty could be negotiated in comfort with many facilities on hand. One example is Merton Priory, which was not too far from Kingston. It was a significant religious centre, and large enough to cater for the retinue of people who came along with the negotiators. They would all need to be fed and lodged. Whereas an island would need a certain amount of effort to get to.

Rivers are often boundaries between land and peoples. This is something that can be traced over hundreds of years. There are theories that the Thames is such a boundary that goes back onto prehistory. Even today, it divides London, with Londoners either being either from south or north of the River. I feel more comfortable in the South.

Islands offer neutrality. By meeting on the River, the parties would not be on either sides’ land. It is difficult to spring a trap, or ambush. You would have to leave your retinue and soldiers on the banks of the River. It would just be the negotiators and their intimate circles who were present in the talks, so no influence from others.

Runnymeade offered a similar neutral place when the Magna Carta was sealed.

Why Kingston?

Kingston in the early 1200s was a very interesting place. Historically it had royal associations. The Saxon town was substantial with a church and a great hall. The very name of it relates to it being a royal place, ie the “King’s town”. Saxon royalty used it as a base, conferences, and some Saxon kings were even crowned there. The royal associations were strong. The Doomsday book in 1089, refers to it as being held by the Crown and it had been at least since Edward the Confessor. King John granted freedoms to the tenants of Kingston in a charter (in 1199) that allowed them to directly rent the land from him, as opposed to work the land for him. This enabled the free tenants to keep their profits and to develop their business interests in other areas.

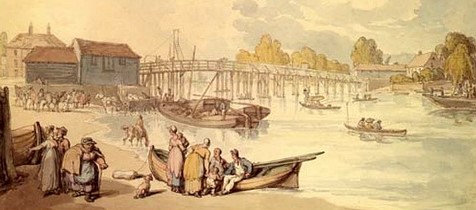

At some point around 1200 a bridge was built across the Thames at Kingston, linking the town to the northern bank. There had been a natural crossing point on the Thames by Kingston, which probably first gave it its strategic importance. A bridge would add further importance to the town. Fording a river could pose risk and delay to journeys. A bridge minimises that and gives certainty to a journey. Although, this bridge was narrow, made of wood, and prone to failure and repairs.

All this considered, the bridge must have been a statement and gave Kingston importance as a destination. Kingston Bridge was the only bridge that crossed the River Thames in the area. The next bridge downstream was London Bridge itself. It wasn’t until the 18th century that other bridges were built reflecting the urbanisation and sprawl of the expanding London. The construction of the bridge made Kingston a strategic location for travel, trade, power and war.

The town must have felt a cosmopolitan and up and coming place. As well as the bridge it had trade, a river connecting it to London, major roads and a market. Did the powerful in the town offer itself as a location for the negotiations? The town would have profited out of it, with the retinue that followed the major players involved in the peace talks. They all would have needed accommodation, supplies, resources and food, all of which would have been paid for.

This makes me wonder whether the chosen location was down to royal favour. The only other strategic location to cross the Thames at the time was London, and London was on the side of the rebels and Prince Louis. Did Kingston offer a “safe” place for royalty. Was it a statement or a message to the authority of London, which held much power in the way of money, trade and autonomy?

To the north of the River

The land on the north side of the bank is interesting. When researching into the background of the treaty, I found a connection linking it to King John. John committed many atrocities, even for that day and age. One of them was against Maud de Braose, wife of William de Braose an English noble, who had been close to John. In 1210, King John imprisoned Maud and her son. Her husband had argued with the King. About what we do not know. He also owed the king a considerable amount of money. To ensure loyalty, the King insisted upon taking Maude’s son, William, as hostage. Maud refused, perhaps worried that the same fate would come to William, as that of John’s nephew, Arthur. Arthur was imprisoned and murdered by John.

King John sent forces to seize William de Braose’s castles in the Welsh borders. Maud and her son fled, but they were later arrested in Ireland, brought back to England and imprisoned in Corfe Castle. They were left in the dungeons and starved to death.

What is the connection? Maud was the daughter of Bernard St. Valery. The St Valery family owned much land in England and had done so since the Norman conquest. This included Spelthorn Manor, the land on the north side of the bank of the River opposite Kingston. Were the St Valery’s loyal to the crown? Bernard died around 1191 and is son Thomas inherited the lands. His relationship, like many of the barons of the time was variable. John did not offer them stability and the leadership they demanded. Thomas supported John’s opponents in Normandy and had his English lands seized. Thomas changed sides several times, regaining and losing his lands. By 1215, he had made his peace with John, but it is possible that he once again changed sides. Although, in 1218, the land passed to Henry of St Albans. He was permitted by Henry III to retain the manor of Hampton. It is possible that Thomas was still on Prince Louis’ side and did not submit to the accession of Henry III. In that case, his lands would have been forfeited in 1217.

To the south of the Thames is Kingston, an up and coming town with royal connections. To the north, is land which had been owned by an established family that rebelled against the crown and supported Louis. The River Thames and Ravens Ait in the middle of the two. Was this a symbolic, neutral space for both sides? Perhaps it was a convenient, practical and diplomatic place to bring the north and south together.

The Treaty

It was a major event in English history. A peace treaty agreed, which led to a long reign of Henry III, although not without complication. Along with the treaty, another outcome was the was a re-drafting of the Magna Carta and the re-issue of 1217, and very importantly a new charter was written, the Charter of the Forest that re-rights of access for freeman to the royal forest.

I feel that I have only just started this research. There are many more avenues I wish to explore, such as the status of Kingston at that time. Not only will I need to establish what Kingston was like in the 12th/13th centuries, but also the wider context of English towns at that time for comparison. In the middle of the 13thcenutry Kingston was granted another charter, that established markets and a fair. Did this happen across England?

The Forest Charter is intriguing, although I have not spent any time on it. It was agreed and sealed as part of the Treaty of Kingston and was a very important document for centuries after. It reflects many aspects of the Robin Hood traditions. Is the Charter deeply integrated into those stories and was there a reflection on the Charter and its value to society a 150 years later, when the stories first started. Incidentally, the fairs granted to Kingston in the 1250s later adopted Robin Hood as its figurehead.

References

Du Garde Peach, 1969, L., King John and Magna Carta, A Ladybird “Adventure from History” Book. Ladybird Books Ltd.

Smith, J. Beverley, 1979. The Treaty of Lambeth, 1217. English Historical Review. Oxford University Press.

Greenwood, G.B., 1971. Kingston upon Thames, a Kingston upon Thames Dictionary of Local History. Martin and Greenwood Publications.

Sampson, J., 1972, The Story of Kingston. Lancet.

Biden, W., 1852, The Histories and Antiquities of Kingston upon Thames.

Love the article!

LikeLike

Thank you Sharon.

LikeLike