I traversed this day, by Steamboat, the space between London and Hungerford bridges… the appearance and the smell of the water forced themselves at Once Upon my attention. The whole of the river was an opaque, pale brown fluid… the smell was very bad, and common to the whole of the water.

Michael Faraday, in a letter to the Times, 1855.

The River Thames looked awful this week. It was brown, murky and a contrast to the beautiful blue skies and shining buildings around it. In fact the colour looks like a muddy landslide. It reminded me of the Thames I first saw in the late 1970s. I was on a London Route Master bus trip, which appeared on the embankment with a view across to the south bank. Both my sister and myself suddenly exclaimed out loud, “Urrrghhh”. It was the Thames we saw. The whole bus must have heard us. This was coming from two rather quiet children, but used to seeing the sea. The contrast between the Thames and the Solent couldn’t have been more stark.

I don’t know why the water was so opaque. Perhaps it was silt washed down river by the previous week’s rain storms. Just over 10 years ago I worked on a programme looking at clean water, using a bit of local, national and international history. Centred around this was the Thames. It made me think, “have moved forward”?

The Thames has been cleared up over the past 30 years. It was polluted and devoid of life back in the 1970s and 1980s. After a few years cleaning, fish were being seen, life had returned as well as a healthy colour. Over the past couple of years that has been undone. Water companies are openly and unashamedly dumping raw sewage into our rivers, including the Thames. A couple of months ago, the famous Oxbridge boat race was compromised when the participants were told not to go in the water due to the health risk. Similarly, there is a question mark about Mud-Larkers working along the banks at low tide, picking out wonderful items deposited in the River Thames over the past 2000 years. Is the lower water mud contaminated?

The Thames was wonderfully clean many hundreds of years ago, right up to the 17th century. It had a plentiful supply of fish that fed the City. But with expansion and industry it was soon heavily polluted by the late 18th century. The City’s infrastructure was basic, and rivers always supply a good means to dispose of your refuse. Much of the refuse and sewage produced within the Metropolis was eventually dumped in the River Thames.

Sweepings from the butchers stools, done, guts, and blood. Drowned puppies, stinking spirits, all drenched in mud, that cats and turnip tops come tumbling down the flood.

Jonathan swift, 1710

The intent was a logical one. The current of the Thames would “flush” the refuse out into the North Sea. That would happen, eventually. But the Thames is tidal and what was dumped in the river, and washed downstream would soon return to join more refuse and sewage that was being discharged into the river.

Drinking Water

Right up until the 20th century, the Thames provided for London in a multitude of ways. It was the fish larder, it was communication and trade to the rest of the world, it linked north and south, and upstream to the west. It provided income, riches, rare goods, spices, silks, and wealth. People from all over Europe came, went and settled in London, brought to the City by the Thames. People from London and England left for new worlds. It was also the source of water for industry and for drinking.

By the 18th century, private water companies supplied their customers with water from the Thames, except for the New River Company which had been piping water from outside the city since the early 17th century. There were plenty of natural springs and wells on the fringe of the City, but these were also becoming poisoned through industry and the increasing population.

The few sewers that existed were small and not capable of catering for a large population. Cesspits were the main way of disposing of household waste, the management of which was struggling under the increasing population.

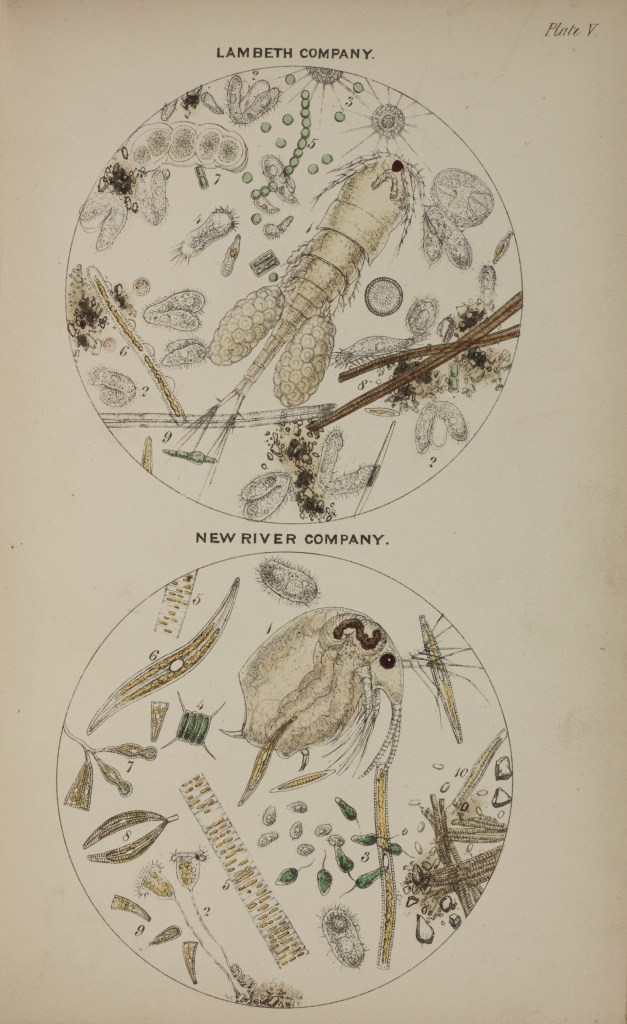

By the 1820s people were fully aware and concerned about the state of the Thames and the water being drawn from it by the water companies. In 1828 William Heath drew the cartoon Monster Soup. In a comic way, it depicts a woman who has looked through a microscope at a sample of Thames Water. Looking straight at the viewer, she drops her cup of tea in shock and horror. It reads “Microcosm dedicated to the London Water Companies. Brought forth all monstrous, all prodigious things, hydras and organs, and chimeras dire.” Beneath the picture it goes on ‘Monster Soup commonly called Thames Water being a correct representation of that precious stuff doled out to us!’ The monsters within the droplet remind me of the medieval imagined “other worlds”, the mythical beasts and creatures that people were terrified of. Perhaps this image is meant to reach down into our psyche to disturb us all.

The Chelsea Water Company was under the spot light in 1827. They drew their water from the River Thames near modern day Victoria. Sir Francis Burdette, MP reported to Parliament:

The water taken from the river Thames at Chelsea, for the use of the inhabitants of the western part of the metropolis, being charged with the contents of the great common sewers, the drainings from dunghills and laystalls, the refuse of hospitals, slaughterhouses, colour, lead and soap works, drug mills and manufactories, and with all sorts of decomposed animal and vegetable substances, rendering the said water offensive and destructive to health, ought not to be taken up by any of the water companies from so foul a source.

Disease

Dirty public drinking water, over-populated slum areas and poor sanitary conditions, led to disease. In 1832, the first epidemic of cholera arrived in Britain. It was followed by outbreaks in 1848 and 1854. During this time, there was much public outcry and fear of the epidemic. No-one knew what to do. The prevailing theory that miasma caused the spread of disease persisted. There were many attempts to protect oneself against cholera, including specially prepared clothing, masks and apparatus that would purify the air. Recipes were devised to cure cholera. One from the first outbreak in 1832 includes castor oil, brine, brandy and laudanum.

This belief in miasma prevailed in the medical profession, to the neglect of sanitary arrangements and water cleanliness; they weren’t looking at the water.

Two decades after Burdette made his comments in Parliament, Arthur Hassal produced a report A Microscopic Examination of the Water Supplies to the Inhabitants of London. He illustrated it with images of the water through a microscope. All of the companies had poor quality water. He concluded:

A portion of the inhabitants of the metropolis are made to consume, in some form or another, a portion of their own excrement, and moreover, to pay for the privilege.

Jon Snow was of course on the case the case of dirty water. His work in Soho around the water pump is famous, and has promoted him to the status of “father of epidemiology”. A more important piece of work was his Grand Experiment, that actually compared clean water filtered and piped in from outside the London area, Seething Wells, against water taken out of the Thames by the Lambeth water company on site. This was a more scientific approach and proved the case of cholera being communicated through water.

Unfortunately, Snow died before his work had influence, with parliament and the medical profession changed direction. The water supply was cleaned up with the Clean Water Act of 1852, and a great super sewer built along the north bank by Bazalgette. This happened only when it personally affected the MPs in parliament. As William Cubett said (1850),

The engineers have always been the real sanitary reformers, as they are the originators of all onward movements: all their labours tend to the amelioration of their fellow men.

The medical profession was still lagging behind.

And today?

This all sounds very familiar now. Rivers are polluted as well as our coastal areas. There is a Super-Super Sewer project on the go and is near finished. As for the water companies, regulation has been relaxed, and our rivers and risk to public heath are sacrificed for capitalism and the free market. Water companies’ main concern are to profits made and dividends to shareholders. Our water is treated before we drink it of course, but don’t go near the rivers themselves. Unless something is changed, what will be the unknowns in the future. Cholera still exists in the world. We just haven’t seen it because of our infrastructure and legislation. If we take that away who knows where this backward progression will take us.

Do we learn from the past…? Hell, no.

Further Reading

You might find this interesting, Another Dirty Book. https://anhistoriersmiscellany.com/2019/01/19/another-dirty-book/

And also…

Heath, William 1828, Monster Soup. The original image can be found in the London Metropolitan Archives and the Wellcome Library.

Barnett, Richard 2008, Sick City,The Wellcome Trust

Hassall, Arthur, 1850, Microscopic Examination of the Water Supplied to the Inhabitants of London

Halliday, Stephen, 2007, The Great Filth, the History Press, Stroud.